Varieties of local textiles have been nurtured in many places in Japan, committing each regional society. We also have local kimono culture to use those textiles. For example, in many manufacturing centres there are technicians called shikkai. These people take care of the entire process of kimono life, from the completion of production to the maintenance after garments are worn. This is a type of Japanese wisdom in order to treasure a piece of textile. There is a line for each kimono to travel from tansu chest to chest which joins owners and generations.

Boro

This clothing in Karamushi Ramie is beautiful with Kasuri splash patterns and must have been a special outfit for the farmers. Although it can hardly be seen from the surface, the fabric has been carefully repaired with patches all over. Ramie is one of the most primitive textiles in Japan but for ordinary people, clothes like this were so precious, and it is fascinating to see the evidence of long-term care in the use of the piece. The Japanese never wasted even a small patch of cloth, and that relationship with textiles is still alive in us in different forms.

At NUNO we produced a patched, embroidered fabric from leftovers and cut waste by adding a few extra processes. The materials go through the process of choosing compatible natural materials, cutting them to the same size, and stitching them together in coordination acccording to their colours. And there you go, the patched fabric looks like lace.

Boro

NUNO Tsugihagi

Oshima Tsumugi

Ōshima-tsumugi (pongee) is famous as a traditional fabric woven by the locally developed extraordinary Shimebata loom which allows a Kasuri (splashed) pattern. Using Sharinbai, a local plant in Amami, and mud full of iron, the Ōshima fabric is dyed in chic, attractive colours. Contemporary Ōshima-tsumugi reflects new ideas, resulting in products such as Shiro (white)-ōshima and Iro-ōshima, expanding the occasions and seasons for wearing this fabric. On Amami-ōshima Island so many business entities are still engaged in the weaving industry and have been treasuring the edge patches of fabric. Using these patches, NUNO’s Ōshima-tsumugi recycled fabric has been created.

Oshima Tsumugi

Twid Gather

Shibori

The oldest tradition among tie-dye techniques in Arimatsu is Miura tie-dye, also called Hiyoko-shibori, Chick tie-dye, because in each dot there is a pattern resembling the shape of young bird spreading its wings. This method is categorized as Kukuri-shibori, Bundling tie-dye, in which cotton thread is tied around the pinched part of the cloth. In order to have a uniform size to the pinched dots, great skill is required.

Inspired by this Bundling tie-dye technique, NUNO’s Tsumami-shibori, Pinched tie-dye, is a contemporary version of shibori textile which took advantage of the thermoplastic nature of polyester, assisted by the new technology of heat transfer print and pleats processing.

Shibori

Tsumami Shibori

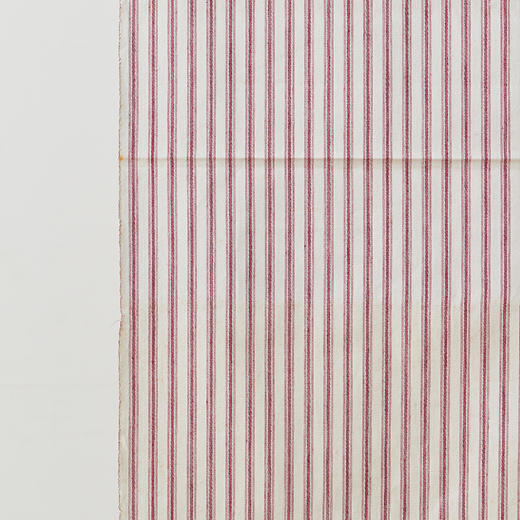

Shimamomen

Aizu cotton is a robust striped fabric worn as farming apparel for generations. Characteristic stripes are woven on an indigo base. There was a special type called Summer Aizu which had white base with a textured surface provided by the twisted weft. The vertical stripes are the most simple, created naturally by the warps in different colours. To make changes in the patterns you must switch warps constantly. But in NUNO’s Domino Stripes product, the vertical pattern is woven only with weft by a dobby loom.

Aizu Momen

Domino Stripe

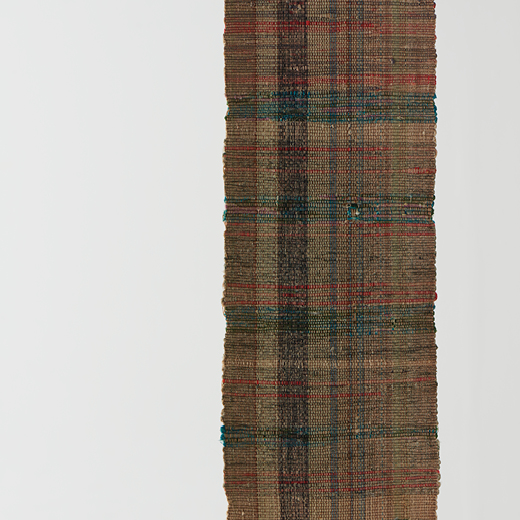

Saki-ori

The weavers are challenged for their ideas and exploring spirit in Saki-ori rag weaving, where any material can be used as warps for weaving with the wefts made of cotton or hemp. It is essentially recycling of the waste, but one can feel the primitive rhythm of the weavers’ joyful heartbeat in the chaotic mixture in stripe-patterned of colours and materials.

Saki-ori rag weaving is ancestral wisdom; as far as the materials can be made thin and long, you can weave in anything. Learning from it and recycling the byproduct, kibiso at the silk-yarn factory, NUNO’s new product was born.

Kibiso, which is the hard part of the cocoon, is utilized and the uneven thickness of the thread resulted in a dynamic fabric.

Saki-ori

Saki-ori

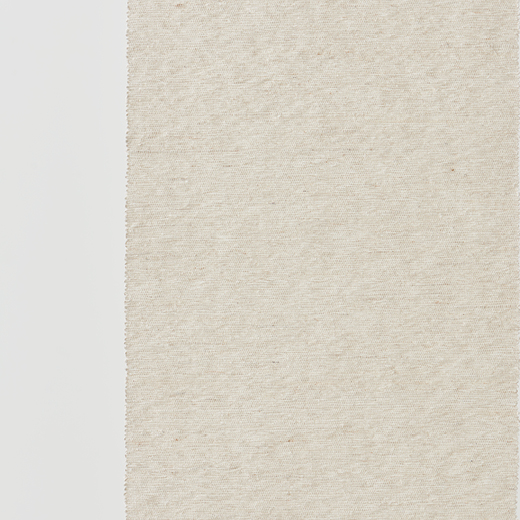

Hand-woven cloth

Bashofu

Ito bashō or Japanese fibre banana plant is raised for three years to peel the outer bark off the trunks. The bark is torn into thin fibers and combined by the extremely labour-intensive process of hatamusubi. The completed thread is dyed with indigo and sharinbai, eventually made into the traditional craft Bashōfu, which is usually decorated with the indigenous kasuri splash patterns such as tuigua or yokadu.

Contemporary industrial processing technology has enabled the reproduction of a practical thread which has the beautiful brown colour of bashō thread. The trunks of wild bashō plants are cut and diluted in alkali, then jellied for application as a coating on the cotton thread. Using these threads, NUNO's contemporary version of Bashōfu is produced in which 80 different units are combined to create intricate stripes while the traditional colours of bashōare preserved.

Bashofu

BASHO 80 Stripe

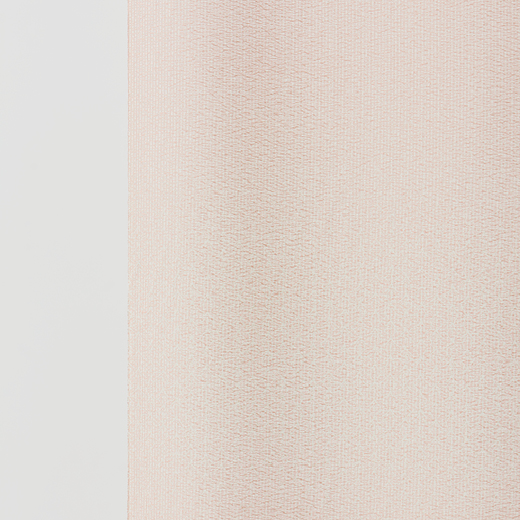

Mojiriori

There is a fabric called Mojiri-ori which is translucent. Its production is very labour-intensive because the method involves cross-twisting the warps during the weaving process. Monsha fabric, woven by the technique passed down in Kyotango, Kyoto, is very delicate and is inspired by the motif of the calm ocean surface.

In Mojiri-ori a machine called a Burue is used for cross-twisting the warps over each other. In the NUNO version of the fabric, the Burue machine is simply set on the loom for wide fabric, so it cannot have a structure as intricate as traditional fabric like Monsha. However, by changing the thickness of the thread and weaving in multiple layers, the curved lines of the warps are emphasized which results in a refreshing modern-looking fabric.

Monsha

Suzushi

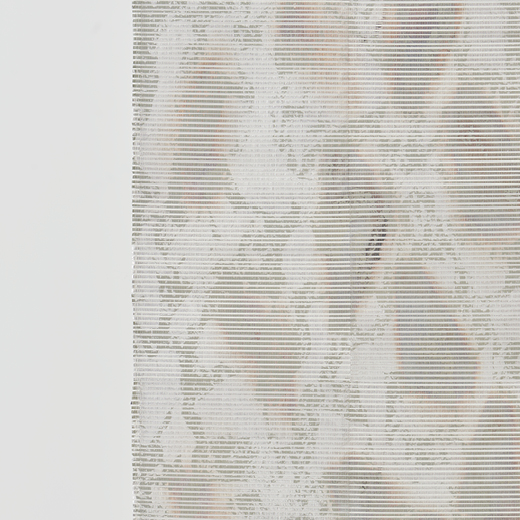

Washi

An attractive stripe-patterned sash called Sanada-obi has been woven in the Shōnai area in Yamagata for women’s use. This fabric is woven using cotton as warp and its weft is made of thinly-sliced twisted washi paper. In the cold area where cotton hardly grew, many kinds of fabric were commonly produced, weaving washi into them. They were worn proudly when women wanted to dress up.

In the NUNO product Ryūsui, the Mino washi is placed freely like running water. In this case the Mino washi can be woven between two pieces of silk organdie without twisting. Mino washi’s thin yet even quality and its durability is a great benefit here.

Sanada Obi

Slipstream

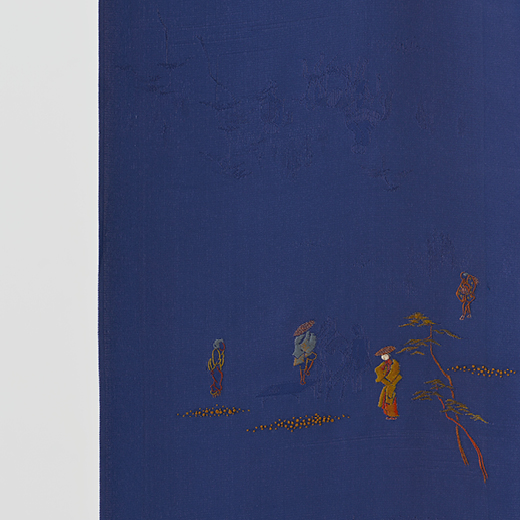

Japanese Embroidery

One of the charcteristics of Japanese traditional embroidery is how the threads are made. A bundle of several silk threads called Kamaito is sewn by hand changing the combination according to the patterns. In addition, the shine of the thread changes depending on how it is twisted. The artisan’s sensitivity controls the effect.

In the contemporary machine-made embroidery called Embroidery Lace, it is possible to place embroidery all over the cloth. As well, separate embroidery can be done freely on top of each other. We can make a fun fabric in which the patterns are scattered and floating unevenly, as if making fluffy motions.

Japanese Embroidery

Fluffy Stars

Metallic foil

Yakihaku is a traditional technique to fix silver foil on washi and then to be oxidized by sulphur. Hikihaku is a technique to weave Yakihaku , which is sliced like thread, without being twisted. The metallic texture can be varied in the surface patterns by different ways of heating. This is an extremely challenging expression in which the artisan’s sensitivity is crucial. For contemporary creations, there are various vapor deposition techniques which have been developed for textiles with metallic textures such as gold or silver foils. Almost any metal can be deposited. For this textile stainless steel alloy was vacuum deposited. Light and flexible like glossy film, this textile is also thermoplastic so that it can be a cloth with geometric designs like origami.

Hikihaku

Spattered Gloss