Modernism was hidden in bathtubs.Three bathtubs by Japanese master designers were surprisingly modern. Perhaps, confronted with the naked body, the designers did not have room to spare themselves for superficial tinkering. Facing these rather vulnerable bodies, honesty brought forward the modernist mentality hidden in these masters’ minds.

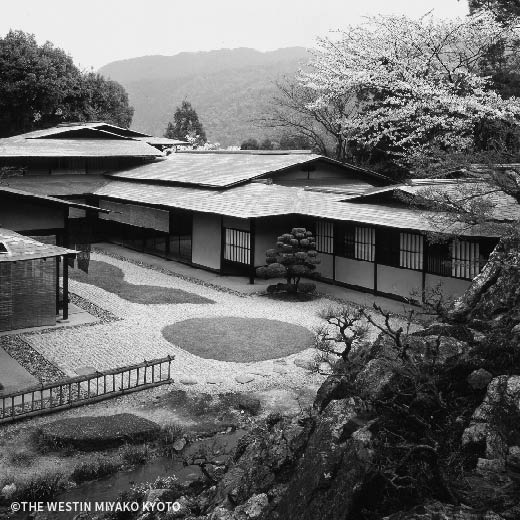

Miyako Hotel Kasuien | Togo Murano

Kasuien is the annex building of the Miyako Hotel And its bath is much smaller than you would think, quite cute. This ryokan is a sukiya-style building which destroys the common prejudice called high-class. The architect uses simple, ordinary ceramic tiles. But he transforms the small bath to sukiya style, by delicately manipulating the gaps of the elements.

Sekirekiso | Isoya Yoshida

In the preparation for commissioning the design of Sekirekiso,the owner,Shigeo Iwanami, took Yoshida to the hot springs in Hakone. And hopping together from one bath to another, so the legend says, they checked how water spilled out when they jumped into the tubs.Overflow could have been the key to this design.the key to this design.

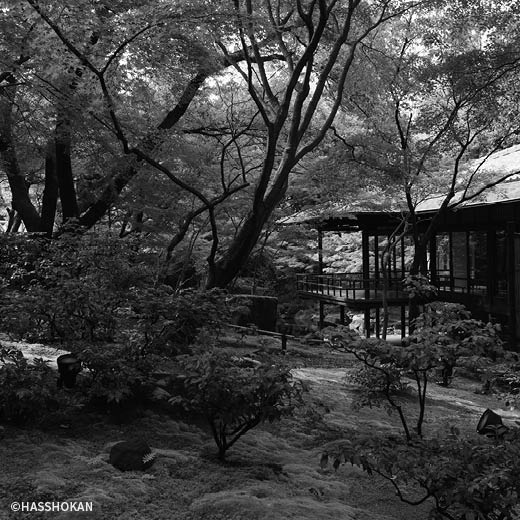

Bathing Pavilion at Hasshokan | Sutemi Horiguchi

Japanese-style buildings by Horiguchi often draw our attention to their intellectual but boorish composition. However, the bath in Hasshokan, known as the Emperor’s Lodging, surprisingly reflects Horiguchi’s early style from his days as a member of Bunriha Kenchikukai. I feel some kind of flashiness like that of an interior designer.